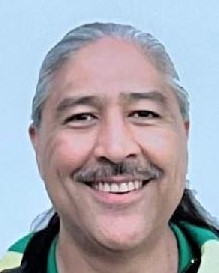

May 7 event will honor Chief Don Ivy

NORTH BEND – The family of Chief Donald Boyd Ivy invites the community to honor his memory on Saturday, May 7, 2022, at The Mill Casino-Hotel.

Family members, friends and colleagues will celebrate Chief Ivy’s life and share memories, both in person and in a tribute film. The event starts at 1 p.m. and will be followed by a reception. Everyone is welcome.

Chief Ivy was born in North Bend in 1951 and grew up in the Empire area. After pursuing a career in retailing and sales, he returned to the Coos Bay area in 1991 to work for his tribe. He was elected as its chief in 2014 and served until a few days before his death on July 19, 2021, after a seven-month battle with cancer.

He is remembered as a dynamic leader and skilled consensus builder. He worked effectively to establish Oregon’s strong inter-tribal and inter-governmental relationships, and he relentlessly pursued economic and educational opportunities for Indian people. By researching and sharing knowledge about tribal culture and history, he encouraged understanding and respect for the heritage of Native American people in Oregon.

A public memorial for Chief Ivy was delayed during the COVID pandemic. Now, with restrictions lifted on public gatherings, his many friends can join his family for an afternoon of recognition and remembrance.

The family requests no photography or recording of the event.

In lieu of flowers, the family asks that donations in Chief Ivy’s memory be given to the Donald Ivy Memorial Scholarship Endowment at Southwestern Oregon Community College. Donations also can be given to the Elakha Alliance, an organization he helped found to restore Oregon’s sea otter population, at www.elakhaalliance.org/donivy/.